Addressing Cross-Border Challenges: The Sudan-Ethiopia Border Dispute and Prospects for Cooperation

October 26, 2025 Rajas Purandare

Abstract:

Since the dawn of the imperial age in Europe, Africa has been a contested ground for colonisation, with British, French, and Portuguese powers taking the lead in the race for dominance since the 17th century. The ongoing border conflict between Sudan and Ethiopia has its roots in the colonial era, with historical territorial claims and contemporary geopolitical dynamics serving as the foundation for disputes between the two nations. The focal point of the Sudan-Ethiopia border conflict is the contested area known as Al-Fashaga, situated at the juncture of Ethiopia's northwestern region and Sudan's Gedaref state.This area is renowned for its fertile lands and abundant water resources, characterised by two peninsula-like features. Furthermore, the article will explore the impact of the border conflict on the lives of civilians, particularly those residing near the border towns, as well as how the conflict has spurred illegal activities in the border areas. It will delve into the ways in which the conflict has shaped regional dynamics and affected neighbouring players. This article provides in-depth insights into how regime change in Sudan, which led to a civil war, has influenced the border dispute. Additionally, it will discuss the impact of the Ethiopia-Tigray conflict on the border dispute. The article will also shed light on efforts made to resolve the conflict.

This study examines the historical background of the border conflict in the region, analysing key border agreements made by British colonialists with the governments of both nations at the time, and their influence on the emergence of various rebel groups and militias. Al–Fashaga, the conflict-ridden region, has led to several economic problems in both countries such as disruption of agricultural practices, loss of livestock, increased costs of living, and overall decline in trade. This article will discuss the various mechanisms to resolve the border issue.

Keywords– Sudan, Ethiopia, border dispute, Al-Fashaga

Introduction –

The Sudan-Ethiopia relationship is complex, involving historical ties, territorial disputes, and contemporary conflicts that have significantly influenced their bilateral relations over time. The bilateral relations between the two nations date back to ancient times. However, formal diplomatic ties were established in the 1960s following Sudan’s Independence. Since then, the relations between the two nations have evolved significantly, particularly after 2011, focusing on deepening economic and diplomatic ties. The current article focuses on the long-lasting Al-Fashaga border dispute between both countries, which further strains relations between both nations, leading to changes in the political, social and economic dynamics of the region.

Historical Background of Sudan –

Since its independence from Britain in 1956, Sudan has been plagued by armed conflicts involving numerous ethnic groups, political factions, and regional tensions. The diverse spectrum of ethnicity, language, and religion in the country, coupled with its abundant natural resources, has been a major factor in fuelling these conflicts. Additionally, competition for power among political elites in the capital city of Khartoum has further aggravated the situation. These factors greatly contribute to the intricacy and continuation of Sudan's ongoing internal struggles.

Since its independence, Sudan has experienced substantial challenges in the process of nation-building. The country's failure to establish inclusive governance and provide fair representation to its diverse ethnic and cultural groups has resulted in political instability. Marginalisation of specific regions, particularly in the south, has contributed to growing resentment and conflict. The country is home to a diverse population comprising various ethnic and cultural groups, all of whom have long sought equal representation and more comprehensive political participation. The marginalisation of certain communities has led to grievances and ethnic divisions, resulting in persistent conflicts that frequently escalate into violence. The population in Sudan is very diverse, with racial, cultural, and linguistic differences among people.

The Sudanese conflict is a highly complex issue with multiple elements and is interpreted differently by various scholars. It is often referred to as a "war of visions" between the riverain North and South and is influenced by multiple factors such as racism, slave treaties, and British policies towards South Sudan. The ongoing conflict in Sudan poses a significant risk to the stability of the Horn of Africa, a region in East Africa that is dealing with various challenges such as insecurity, political turmoil, and humanitarian crises. Countries in the region, including Somalia, Ethiopia, and Djibouti, are closely monitoring the developments in Sudan, especially as the region has become a focal point of global competition for influence in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.

Historical Background of Ethiopia –

Ethiopia was ruled by successive Emperors until 1974. Haile Sellasie, the last emperor, was ousted and was replaced by a pro-Soviet Marxist–Leninist military junta, the Derg, led by Mengistu Haile Mariam. The Dreg established a one-party communist state that ruled the country among intra- and interstate conflict and coup attempts for 17 years.

In May 1991, the Derg was ousted by the rebel coalition EPRDF (Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front), with the dominant TPLF (Tigray People's Liberation Front) playing a key role. During the struggle against the Derg, various rebel groups with distinct objectives united to confront their common adversary.

As some groups were separatists, an attempt at creating a new, more decentralised constitution was made after the Derg was ousted. A transitional Government of Ethiopia was set up, dominated by the EPRDF, which subsequently ruled Ethiopia for four years. During this period, far-reaching reforms were made, with a market economy being introduced and state-owned companies privatised.

Historical dynamics of cross-border trade between Ethiopia and Sudan (1974 – 1991) –

Historically, the Metema- Humera and Quara border regions were placed under three administrative units: Wogera Awraja, Gondar Awraja and Chilga Awraja of Begemidir and Simien Governorate General, which were scenes of several historical processes and political dynamism in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Political tensions between Ethiopia and Sudan during the Derg regime significantly influenced contraband trade in the Metema–Humera corridor. Factors like governance, political interests, and armed conflicts resulted in illicit trade.

Fragile Governance - In the border regions, political unrest and the activity of multiple armed groups posed significant challenges to governance and security. The local police forces were often outnumbered by insurgents and heavily armed smugglers, leading to numerous attacks on security personnel and customs locations. This volatile situation enabled illegal traders to operate without fear of punishment, thus facilitating the illicit movement of goods over the border.

Corruption - Plans to control contraband trade were poorly implemented due to corruption and a lack of commitment from both the Ethiopian and Sudanese governments. Treaties signed in 1980 and 1981 to regulate cross-border trade were not respected, further exacerbating the situation. The ineffective policing and the presence of corrupt officials allowed contraband trade to flourish.

Economic Factors - The price variations for goods between border regions and highland markets prompted an increase in contraband trade. For instance, the high demand for Ethiopian cattle in Sudan resulted in a rise in cattle theft and smuggling, as traders attempted to take advantage of these economic discrepancies. The impact of contraband trade extended beyond local economies and had significant implications for Ethiopia's national revenue.

Diplomatic Ties - Although there were temporary improvements in relations between Ethiopia and Sudan in the early 1980s, these did not lead to lasting solutions for the issues at the border. The lack of effective diplomatic engagement meant that contraband trade continued to escalate, driven by the ongoing political instability and economic motivations.

Objectives of the study:

-

To identify and understand the border issue between Sudan and Ethiopia

-

To study the causes and effects of the conflict in the region.

-

To highlight agreements regarding the dispute.

-

To study any possibility of resolving the issue.

Methodology - The following secondary data in the form of research articles, research papers, and newsletters, have been used to understand and analyse the conflict border dispute.

Timeline of Key Events –

-

1902 – British-controlled Sudan and the Ethiopian Empire agreed to a border demarcation that placed most of Al-Fashaga within Sudan, although Ethiopian farmers continued to cultivate the land and pay taxes.

-

1907 - Delimiting the boundary between the East Africa Protectorate, Uganda, and the Ethiopian Empire. The border was defined as proceeding from the confluence of the Dewa and the Ganale-Darya in Somalia to the northeast coast of Lake Rudolf (Turkana), ceding large areas that had formerly been claimed by the British East Africa Protectorate to Ethiopia. Although Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia signed the agreement, he never ratified it due to ill health, and the boundary would not be formally demarcated until the 1950s.[1]

-

2008 Compromise – Ethiopia and Sudan agreed that Sudan would have administrative control, but Ethiopian farmers could remain and cultivate the land undisturbed, creating a functional though uneasy modus vivendi.

-

November 2020 – Beginning of the Tigray war in northern Ethiopia; Amhara militia and federal forces redeployed to Tigray. Sudan launched a military operation to reclaim Al Fashaga, expelling thousands of Ethiopian farmers and collapsing the 2008 compromise.

-

November 2022 – Ethiopia reached a Cessation of Hostilities Agreement to end the Tigray War, despite this, the Al-Fashaga border remained a point of dispute with no new progress towards its resolution.

Tigray Conflict –

The election of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed in 2018 marked a significant shift in Ethiopia’s political landscape. The change disrupted an established political hierarchy since the Fall of the Mengistu regime. The reshuffling of ethnic balances within the government led to the sidelining of the formerly ascendant Tigrayan ethnic elite in favour of ethnic Amhara factions.

Tensions between Ethiopia’s three major ethnic groups - Oromos, Amharas, and Tigrayans are long-standing and underpin this civil war. The conflict has spanned several phases. Following the initial occupation of Tigray, the TPLF undertook a massive mobilisation and successfully recaptured the city of Mekelle in June 2021 and later advanced towards Addis Ababa. In November 2021, they retreated to Mekelle, after which the Eritreans, Ethiopian National Defence Forces (ENDF), and Amhara militias launched their final offensive.

The assault ended with the signing of the Cessation of Hostilities Agreement (CoHA) in November 2022. The CoHA facilitated the restoration of constitutional order in Tigray, enabling federal authorities, including the Ethiopian National Defence Forces, to resume their normal functions in the region. While TPLF is recognised as a rebel group, the agreement will enable it to survive as an organised political entity by promising its delisting as a terrorist organisation.

The agreement also signifies a shift in the balance of power, marking the decline of TPLF's political significance at the national level and consolidating the power of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and his ruling party. According to researchers at Ghent University in Belgium, as many as 600,000 had lost their lives because of war-related violence and famine by late 2022. (Mishra, A., 2024)

Regional Players in the Tigray Conflict –

Kenya -

The bilateral relationship between Kenya and Ethiopia remained stable during the Tigray conflict, while Kenya highlighted the humanitarian, economic and regional security implications of its neighbour’s territory. Kenyan officials repeatedly stated that the government sought to prevent the disintegration of Ethiopia at any cost and reiterated the importance of prioritising engagement through the African Union. Kenya’s interest in reducing the conflict lies in its economic interest. Kenya’s Safaricom was awarded a license to operate telecommunications services in Ethiopia in May 2021, for $850 million, making it the single largest foreign direct investment in Ethiopia at that time.

Kenya benefited from Ethiopia’s suspension from the United States African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) preferential trade program in 2022. In the context of the Tigray conflict, Kenya is also home to the largest number of Ethiopian refugees in Africa. During its peak political crackdown in 2021, thousands of Ethiopians sought asylum in Kenya. In March 2022, Ethiopia appointed Major General Bacha Debele, a controversial military figure associated with the Tigray War, as its ambassador to Kenya. This signalled a significant shift in Ethiopia’s diplomatic policy towards Kenya. They were reflecting the increased focus on security and economic priorities.

Egypt –

Ethiopia’s relations with Egypt can be characterised by its long-running tensions, mainly focused on the Nile River. Both countries have a population exceeding 100 million for whom the Nile serves as a vital resource. For Egypt, water security is an essential issue as 95% of its population resides near the Nile River Basin, while Ethiopia views the Nile River as a hydroelectric potential, particularly associated with the Grand Ethiopian Resistance Dam (GERD). Egypt excluded Ethiopia from the Red Sea Council, a forum established to foster cooperation among littoral states on security issues and enhance stability in the region.

Egypt has implemented a strategy of encirclement against Ethiopia, which includes the establishment of defence cooperation agreements and the planned deployment of Egyptian forces in strategic locations such as Eritrea and Djibouti. These actions are aimed at exerting pressure on Ethiopia, furthering overarching security objectives concerning the Nile River.

The issue of sharing land and resources:

The region of Al-Fashaga is of great importance to Ethiopia’s Amhara state as it shares a border with it. As Ethiopia’s population is increasing rapidly, the control of the region has become even more crucial. The number of people in Amhara has grown to over 20 million. As a result, access to land and other resources for sustaining livelihoods has become an urgent issue. In 2008, a compromise was achieved between the two nations, recognising the border established in 1907 and allowing Ethiopian communities to persist in their residence and agricultural activities in Al-Fashaga. However, this lenient border delineation increased the number of Ethiopians seeking employment and arable land, exacerbating local conflicts over land and resources. The problems inside both countries, especially the crisis in Ethiopia's Tigray region, have worsened the situation. Both countries might use this conflict to gain more control within their borders, which could lead to a bigger conflict.

Al-Fashaga: The Heart of Conflict –

The Al-Fashaga dispute dates to the early 20th century. This 260km area spans the borders of Eritrea, the Ethiopian regional state of Amhara, and the Sudanese region of Gedaref. The British and Emperor Menelik 2 of Ethiopia established the 800km long borderline between 1902 and 1907. The decision to run the border eastward led to ambiguous interpretations, similar to other border agreements in the Horn of Africa, such as the Ethno-Somali border known as the Haud.

The Al-Fashaga region holds historical significance for both Sudan and Ethiopia, as each country has longstanding claims over the area. Notably, the Ethiopian Amhara community regards Al-Fashaga as an integral part of their territory from a historical standpoint, which fuels their desire to reclaim what they perceive as their ancestral land. The Al-Fashaga region is an essentially agricultural area, often described as the "breadbasket". The competition for land and resources, especially considering growing scarcity, has increased tensions between the two countries. The capacity to support livelihoods in this region is crucial for Ethiopian and Sudanese communities.

Picture Courtesy – https://issafrica.org/iss-today/ethiopia-sudan-border-tensions-must-be-de-escalated

Armed conflict in Al-Fashaga has led to significant displacement of populations. Neighbouring states may need an influx of refugees fleeing the violence. This could strain resources and create humanitarian challenges, necessitating international assistance and cooperation among neighbouring countries.

The Amhara are Ethiopia’s second-largest ethnic group in the country, making up about 27% of Ethiopia's population. Around 1995, Sudanese forces turned their attention towards another disputed area with Egypt known as the Halayeb Triangle, and at the same time, a large number of the Amhara population moved into Al-Fashaga, quickly seizing control of the most fertile lands in the territory.

The 2008 agreement between Ethiopia and Sudan regarding cooperation over Al-Fashaga was primarily dependent on the positive relationship between the leaders of both countries. Meles Zenawi, the Ethiopian leader who led the rebel coalition in 1991, fostered close ties with Omar Al-Bashir, his Sudanese counterpart. Meles began to strengthen diplomatic relations by isolating Eritrea after its relationship with Ethiopia soured due to a two-year border war (1998-2000) that resulted in significant loss of life.He also sought Sudan's backing for the GERD (Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam), which is the largest hydropower plant in Africa and is located approximately 20 kilometres from the Sudanese border. The dam has been a source of occasional tension between Ethiopia and its downstream neighbours, Sudan and Egypt, due to reduced water flow during reservoir filling.

Efforts to establish clear boundaries in the 2000s consistently faltered when surveying teams reached Al-Fashaga. However, the 2008 cooperation agreement included a compromise that permitted both Sudanese and Ethiopian citizens to cultivate crops, graze cattle, and engage in trade in the area. As a result, thousands of Ethiopians migrated across the border into Al-Fashaga to work as daily farm labourers.

Apart from this deal, multiple other agreements regarding land use and crop sales at the state, district, and local levels provided a foundation for cooperation. Ethiopia incentivised farmers in Al-Fashaga, especially Ethiopians, but also Sudanese, to sell their crops to Ethiopian marketing boards, making it more lucrative for them to conduct business in Ethiopia.

Conversely, Sudan did not offer similar incentives. For over a decade, Sudanese and Ethiopian farmers coexisted in relative harmony in the region. However, in 2020, believing that hostilities were unlikely, Ethiopia started pulling out a number of people from al-fashaga to participate in the Tigray war.

With Ethiopia distracted in the Tigray War, Sudanese troops moved into Al-Fashaga., shortly after it began evicting Ethiopian farmers and building fortified military outposts. The rapid large-scale deployment of troops indicates that Sudan likely had prepared for an incursion into Al-fashaga well before Ethiopia was distracted by the Tigray war. Ethiopia deployed federal troops and militia in response, but Sudanese troops swiftly advanced, taking control of the Khor Yabis area, which Ethiopia had held for 25 years. Shortly afterwards, Sudan also occupied Jebel Tayara in the Eastern Quallabat locality, pushing deeper into Al-fashaga.

Since the start of their incursion in November 2020, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) have gradually gained control of up to 95% of the disputed border territory. They have strengthened their presence with significant infrastructural developments, including the construction of bridges across the Atbarah River and the establishment of military outposts between 2020 and 2022. Ethiopia’s restraint at Al Fashaga forms a part of its broader regional strategy encompassing regional stabilisation, counter-insurgency efforts against movements such as the Fano insurgency, and maintenance of fragile post-war arrangements in Tigray. By avoiding escalation, it seeks to present itself as a responsible regional actor, prioritise diplomacy over military action and preserve its long-term strategic objectives, including safeguarding trade routes and preventing insurgent groups from using Sudanese territory as operational bases.

The GERD –

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), located on the Blue Nile in Ethiopia, is a significant hydropower project that has been a focal point for regional tensions among Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan. The GERD was initiated in 2011 and completed its second filling phase in July 2021. Located in the Benishangul-Gumuz region of Ethiopia, the dam has sparked tensions between Egypt and Sudan, both of which are downstream countries relying on the Nile's water. With a planned capacity of 6,450 megawatts, it is projected to double Ethiopia’s electricity production, thus benefiting a population where only half currently has access to electricity. As a result, it is expected to drive Ethiopia’s economic growth and diversification.

Egypt, a predominantly arid nation, relies on the Nile River for 90% of its water supply to support domestic, agricultural, and irrigation needs. Egypt has historically maintained exclusive control over the Nile River stemming from two colonial-era treaties: the 1929 Anglo-Egyptian Treaty and the 1959 Nile water agreement between Egypt and Sudan.

However, upstream nations, including Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, and Uganda, have recently disputed their non-involvement in these agreements. Egypt is deeply concerned about the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) as it poses a threat to the amount of water that flows into Egypt from the Nile River. With over 100 million Egyptians relying on the Nile for their water needs, the Egyptian government is seeking a fair agreement on the filling and usage of the dam. They fear that Ethiopia's independent actions regarding the dam could potentially harm Egypt's water supply.

Sudan often takes a balanced stance on the issue, given its geographical location between the upstream country, Ethiopia, and the downstream country, Egypt. While acknowledging the potential benefits of the GERD, such as increased water flow during the rainy season and potentially reduced flooding, Sudan also expresses concerns about the dam's impact on its water resources and agricultural needs. Unlike Ethiopia, which sees the dam as a crucial development project, and Egypt, which considers it a threat to its water security, Sudan's stance is influenced by its unique geographical and hydrological context.

On 9 September 2025, Ethiopia formally inaugurated the GERD, Africa’s largest hydroelectric facility, marking a pivotal moment in the country’s infrastructure and energy development agenda. It is situated on a tributary of the Nile River, positioned as a cornerstone of Ethiopia’s economic modernisation strategy, and it is expected to supply electricity to millions of citizens.

With an installed capacity of 5,100 megawatts, achieved following the progressive activation of turbines since 2022, the GERD now ranks among the twenty largest hydroelectric dams globally, producing approximately one quarter of the output of China’s Three Gorges Dam. [2]

Image Credits - https://www.hindustantimes.com/world-news/the-promise-and-peril-of-ethiopia-s-new-megadam-101757410927427.html

While the Ethiopian government presents GERD as integral to national development and energy security, the project has intensified tensions with Egypt. It has expressed concerns that the dam could reduce its share of Nile waters during drought periods and set a precedent for additional upstream water infrastructure projects. The ongoing Nile dispute exemplifies a complex geopolitical competition between Ethiopia's pursuit of hydroelectric power and Egypt's imperative to safeguard its water resources. Without overcoming political biases and establishing a collaborative water-sharing arrangement for the Nile basin, there is a significant risk of escalating conflict between the nations.

Strategic Interlinkages: GERD and the Al-Fashaga Dispute –

The Tigray conflict, which erupted in 2020, significantly transformed the regional dynamics surrounding the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). In the wake of the civil war in Tigray, Sudan's position shifted considerably. Previously acting as a mediator between Egypt and Ethiopia in negotiations related to the GERD, Sudan adopted a more assertive approach following the outbreak of conflict. This has led to suspicions that Egypt, potentially leveraging Sudan’s involvement, may have provided support to the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF).Amid these developments, Sudan moved to reclaim the contested Al-Fashaga borderlands, which Ethiopian farmers had long cultivated under military protection. This territorial repositioning has enabled Sudan to maintain control over a specific area. Consequently, Sudan retains the area from where a humanitarian corridor can be opened into Tigray since Ethiopia has blocked the southern routes into Tigray. Ethiopia resists this.[3]

Both Egypt and Sudan are united in demanding that Ethiopia agree to a legally binding agreement on the management of Nile waters rather than relying on mere guidelines. They also seek clear mechanisms for resolving future disputes. Tension has indeed increased in the region, especially since the Tigray war and weakening of Ethiopian state capacity have affected the regional balance of power.

Sudan leverages its GERD position to increase bargaining power against Ethiopia on the Al Fashaga border dispute. By shifting cooperation and tough rhetoric on GERD, Sudan signals it can escalate Nile water disputes if Ethiopia does not yield on its Al Fashaga dispute. Between cooperation and tough rhetoric on GERD, Sudan signals it can escalate the Nile dispute if Ethiopia does not yield its Al Fasahga claims.

Ethiopia has emphasised the GERD as a unifying project, seeking to bolster domestic cohesion when the civil war in Tigray weakened the national solidarity. The dam has emerged as a central symbol of Ethiopian national pride, albeit one conceived and initiated under the country’s previous leadership, which the current administration has publicly distanced itself from.

Conditions of People Living on the Sudan-Ethiopia border –

Refugees in Ethiopia, particularly in the Amhara region, are enduring dire living conditions. Following violent incidents, including attacks and abductions within refugee camps, many have sought refuge in forested areas. Reports from 2023 indicate that approximately 4,250 refugees are currently stranded in a forested environment, facing threats from both wildlife and local militias. Refugee camps such as Awlala and Kumer are characterised by the absence of essential services and heightened security risks, including shootings and physical assaults.

In June 2024, there were reported Ethiopian militia attacks in the Tayah region, Al-Quraisha locality, on the border strip in the Gedaref state in eastern Sudan. The Ethiopian militias impeded the movement of Sudanese herders in the area and killed one of the herders. Additionally, hundreds of heads of cattle were looted and taken into Ethiopian territory.

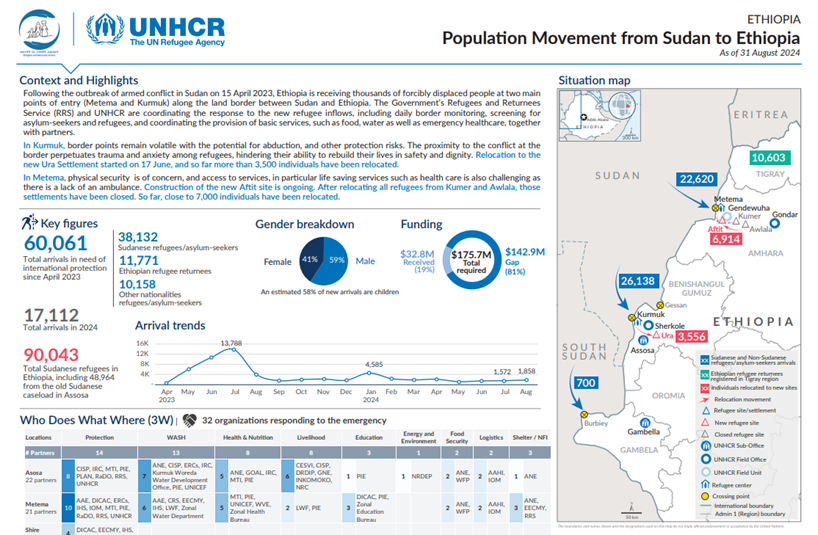

The refugee crisis of Sudan Ethiopia Border –

Image Credits - https://reliefweb.int/report/ethiopia/unhcr-ethiopia-population-movement-sudan-ethiopia-31-august-2024

However, somewhere between 10,000 and 12,000 refugees remained in Hamdayet. This has led to a severe economic toll on the already struggling economy of Sudan, which has the responsibility to host, feed and safeguard thousands of refugees.

Effects of the Al-Fashaga Conflict –

Humanitarian Crisis –The ongoing conflict has led to a severe humanitarian crisis. As per 2023 data, over 2.8 million people have been displaced from Sudan due to escalating conflict, and the conflict has led to thousands of deaths, with estimates of at least 5,000 fatalities. Since the beginning of the conflict, 19 humanitarian workers have been killed and 29 have been injured. According to the WHO (World Health Organisation), 11 health workers have been killed and 38 have been injured.(https://reliefweb.int/report/sudan/glance-protection-impact-conflict-update-no-13-6-august-2023) There has been a 30% increase in acute malnutrition cases in the conflict-affected areas. Acute malnutrition has also increased by 15% in localities hosting the displaced people and 10?ross the rest of the country. In Gedaref, approximately 247,980 internally displaced persons (IDPs) from Khartoum have sought shelter in Al Mafaza, Al Fao, and Al Fashaga. These IDPs are residing in informal hosting arrangements, primarily in rented accommodations.

Impact on the Economy –

Looking at the agrifood scenario during the conflict, the sesame trade is an important part of the economy in the border region. Local agricultural markets are looking towards controlling the sesame revenues due to which there is strategic motivation for conflict participants. The profits from the sesame trade are used by the Sudanese army, and it has helped to develop their military. This is hampering the efforts of the local Sudanese and Ethiopian farmers.

The violence caused by the conflict has affected the local livelihood in numerous ways. The border between Gallabat in Sudan and Matama in Ethiopia has been closed during the conflict. This has weakened the opportunities for interactions between the two communities across the border. Earlier in the conflict, the legalities were followed for the transport of goods, which has now turned into human trafficking and smuggling of goods.

Conclusion –

Resolving intricate disputes presents considerable challenges. It is imperative to prioritise the de-escalation of tensions before initiating negotiations, a task that both Ethiopia and Sudan should regard as essential. Ethiopia and Sudan possess multiple mechanisms to solve the dispute without resorting to conflict or proxy war. They may engage in bilateral negotiations, seek involvement of third-party mediators, or, if other options prove ineffective, resort to international arbitration as a last resort.

The African Union, via its special envoy to Sudan, Mohamed Hassan Lebatt, who visited Khartoum in February 2021, has urged both Ethiopia and Sudan to reduce tensions and pursue a political resolution to their dispute. However, the special envoy currently lacks a mandate to engage in mediation between the two nations. In contrast, the African Union High-Level Implementation Panel for Sudan (AUHIP), chaired by former South African President Thabo Mbeki, possesses the mandate to intervene in such disputes. Nevertheless, the AUHIP has experienced a decline in support from key political actors in Sudan, as evidenced by its exclusion from the political transition process.

To achieve a peaceful resolution to the Al-Fashaga dispute, a comprehensive approach is necessary. This conflict, which occurred between 2020 and 2022, led to disengagement and de-escalation, resulting in Sudan regaining control of the entire border territory. In 2021, Al Burhan and Prince Mohammed bin Zayed held a bilateral meeting to discuss initiatives regarding the border dispute between Sudan and Ethiopia, as well as the stalled Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. Security cooperation to address mutual threats was also a topic of discussion, although the Al-Fashaga region was not specifically addressed. In May 2021, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) officially withdrew from its initiative to mediate in a dispute over Sudan's border with Ethiopia.

It is imperative for Addis Ababa and Khartoum to refrain from rapid military deployments to the border area to address these issues. International partners should advocate for a peaceful resolution. Many experts propose a flexible border arrangement that accounts for the needs of farmers from both countries. Behind the geopolitical narratives lie the everyday struggles of ordinary farmers. Communities in the region face disrupted harvests, militarised checkpoints, and the transformation of once commercial routes into conflict lines. For these populations, Al Fashaga is less about diplomacy and more about daily survival; the presence of armed forces, operating with limited oversight from either government, exacerbates and heightens the risk of escalation.

Efforts by regional bodies such as the AU and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) have so far been limited to calls for dialogue and descalation. These attempts have not yielded a durable solution, underscoring the need for a more robust and multilayered diplomatic effort. Resolving the Al Fashaga dispute necessitates more than bilateral negotiations; it requires a comprehensive framework incorporating diplomacy, legal demarcation, and soft border management, as well as community-centred strategies. By combining these elements, Ethiopia and Sudan can shift from confrontation to cooperation, transforming Alfasahga from a flashpoint into a mode of cross-border stability and development.

Bibliography -

- Abebe, Y. (2021). Contemporary geopolitical dynamics in the Horn of Africa: Challenges and prospects for Ethiopia. *International Relations and Diplomacy, 9*(4), 229-245. David Publishing.

- Africanews. (2022,). Sudan-Ethiopia army clash at disputed Al-Fashaga border after attack that killed Sudan soldier. Retrieved September 9, 2024, https://www.africanews.com/2022/06/29/sudan-ethiopia-army-clash-at-disputed-al-fashaga-border-after-attack-that-killed-sudan-sol

- Al Jazeera. (2021,). Sudan and Ethiopia trade barbs over border dispute. Retrieved September 9, 2024, from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/2/20/sudan-and-ethiopia-trade-barbs-over-border-dispute

- https://reliefweb.int/report/sudan/glance-protection-impact-conflict-update-no-13-6-august-2023

- Alredaisy, S. (2024). The physical geography of Sudan: A state’s power and threats. *International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews, 5*.

- Ayferam, G. (2024). Perspectives on the geopolitical implications of post-1991 Ethiopia's hydropower development. *African Journal of Politics and Administrative Studies*.

- Chr. Michelsen Institute. (n.d.). The Sudan-Ethiopia border: Needs a soft border solution. Retrieved September 9, 2024, from https://www.cmi.no/publications/8191-the-sudan-ethiopia-border-needs-a-soft-border-solution

- Çınar Yıldırım, H., & Özer, A. (2023). Internal and external factors behind the instability in Sudan. *Perceptions: Journal of International Affairs, 28*(1), 173-193.

- Desai, N., & Munroe, C. (2021). *Borders and the new geopolitics*. Centre for International Governance Innovation.

- Ding, L. (2024). *The evolving roles of the Gulf states in the Horn of Africa*. Routledge.

- Engida Erkihun Alemayehu. (2024). Nexus of political tensions and cross-border contraband trade between Ethiopia and Sudan, 1974–1991: Evidence from Metema Humera corridor and its environs. *Cogent Arts & Humanities*.

- European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations. (n.d.). Border Sudan conflict forces thousands to flee Ethiopia. Retrieved September 9, 2024, from https://civil-protection-humanitarian-aid.ec.europa.eu/news-stories/stories/border-sudan-conflict-forces-thousands-flee-ethiopia_en

- Ezugwu, O., & Duruji, M. (2023). Tigray conflict and political development in Ethiopia: Assessing governance, political participation and human rights. *Journal of African Conflicts and Peace Studies, 5*(2), 1-22.

- Gebresenbet, F., & Tariku, Y. (2023). *The Pretoria Agreement: Mere cessation of hostilities or heralding a new era in Ethiopia?* Routledge.

- Gebrewahd, M. (2023). The war on Tigray: Geopolitics and the struggle for self-determination. *Hungarian Journal of African Studies, 17*(3).

- Goitom, G. (2014). *Ethiopia's Grand Renaissance Dam: Ending Africa's oldest geopolitical rivalry?* Routledge.

- Gregoire, R. (2024). Sudan’s current conflict: Implications for the bordering regions and influence of the key regional/international actors. *Journal of Social Encounters, 8*(1), 45-61.

- Mishra, A. (2024). Emerging security competition and challenges in the Horn of Africa. *MP-IDSA Issue Brief*. Manohar Parikar Institute of Defence Studies and Analysis.

- Najimdeen, H. (2023). *Sudan’s crisis and the implications for its neighbours*. Al Jazeera Centre for Studies.

- Puddu, L. (2017). Border diplomacy and state-building in northwestern Ethiopia, c. 1965–1970. *Journal of Eastern African Studies*, *11*(1), 98-115. Routledge.

- Tamirat, W., & Muluken, A. (2023). *Ethio–Sudan bilateral diplomatic relation since 2011: Review on economic relation*. Taylor and Francis.

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-56799672

About the Author:

Rajas Purandare is working as a Researcher at the Indic Researchers Forum. He holds a MA Hons. in International Relations & Strategic Studies from the University of Mumbai.

Note:

The research paper reflects the opinion of the author and not necessarily the views of the organisation.

Share this article:

© Copyright 2025 Indic Researchers Forum | Designed & Developed By Bigpage.in