State recognition in International Law - A case study of Kosovo

March 04, 2022 Anshu Singh

I.Introduction

Research problem: The problems confronted by a new country that declared its independence from another country, in this paper author has discussed obstacles faced by Kosovo as a newly independent country seeking international recognition.

Objective: The objective of the paper is to understand the State recognition in international law and Kosovo has been taken as a case study.

In international law, a new state may be formed from part of the territory of an existing state and its creation, and recognition by other states, will be lawful if this occurs on the basis of the consent of the ‘parent’ host state. Statehood in the early 21st century remains as much a central problem as it was in 1979 when the Creation of States in International Law. As Rhodesia, Namibia, the South African Homelands. Today governments, international organizations, and other institutions are seized of such matters as the membership of Cyprus in the European Union, application of the Geneva Conventions to Afghanistan, a final settlement for Kosovo.

Self-determination and secession constitute central issues of international law. Peoples and minorities in many parts of the world assert a right to self-determination, autonomy, and even secession which conflicts with the respective mother states ’sovereignty and territorial integrity. Apart from its practical relevance, this conflict also demonstrates how modern visions of international law, promoting rights of individuals and groups against the state, might clash with older visions that emphasize the role of the sovereign state for the protection of stability and peace. After the Advisory Opinion of the International Court of Justice concerning the Declaration of Independence of Kosovo, rendered in 2010,1 many questions of self-determination and secession remain open. 1

Recognition of state under the International Legal System can be defined as “the formal acknowledgement or acceptance of a new state as an international personality by the existing States of the International community”. 2 It the acknowledgement by the existing state that a political entity has the characteristics of statehood.

Under the International Law, Article 1 of the Montevideo Conference, 1933 defines the state as a person and lays down following essentials that an entity should possess in order to acquire recognition as a state 3:

-

It should have a permanent population.

-

A definite territory should be controlled by it.

-

There should be a government of that particular territory.

-

That entity should have the capacity to enter into relations with other states.

Theories of recognition

Two main theories are given under the international law for the recognition of a state, which are:

-

Consecutive Theory This theory simply said that a state requires recognition from the existing sovereign states to become an international person. Only after the recognition of other states, a state becomes the subject of international law and recognized as an international person. According to this theory, even if a state has all the essentials which are required for the recognition, the state would not become subject to international law except recognized by other existing states.

-

The theory doesn’t mean that a state cannot exist without the recognition given by other states, but the state can only get the exclusive rights and duties after its recognition by existing sovereign States. 4

2.Declaratory Theory

The proponents of the declaratory theory are Wigner, Fisher, Hall, and Brierly. The theory said that a new state is independent of the consent by other sovereign states. This theory was laid down under article 3 of the Montevideo Conference in 1933. According to this theory, the new state can exist even without the recognition by other states and the new state has the right to defend its integrity and independence under international law. The followers of this theory consider the recognition by other states as the formality of statehood.

Methods of Recognition

There are two methods of acknowledgment of State:

-

De facto Recognition

-

De Jure Recognition

De facto Recognition is a temporary acknowledgment of statehood. This is the first step of De Jure’s recognition. In the De Facto Recognition, the new state has held the sufficient territory and population, but the other states consider that the new state does not have stability or any other essential which it must have, so the existing states give its formal recognition that if the new state will pass to fulfil the required essentials, the other state will consider it as state after that.

De jure recognition is the acknowledgment of a new state by the other state after the fulfilment of essential given under the international law. The existing state can give its de jure recognition either with or without the de facto [Recognition]. The De Jure recognition can only be given to a newly formed state when a new state acquires all the essentials to become a state . 5

We can say that the recognition of a new state is useful for the state to become a subject of international law. The state can enjoy its rights and duties after the [Recognition]. Though there is the controversy between the theories of the recognition of state but the existing states are using harmonious (Recognition), which means they are using the theory between both the theories.

II.Background of Kosovo

In the 20th century; First partitioned in 1913 between Serbia and Montenegro, Kosovo was then incorporated into the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (later named Yugoslavia) after World War I. During World War II, parts of Kosovo were absorbed into Italian-occupied Albania. After the Italian capitulation, Nazi Germany assumed control over Kosovo until Tito’s Yugoslav Partisans entered at the end of the war. 6

After World War II, Kosovo became an autonomous province of Serbia in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (S.F.R.Y.). The 1974 Yugoslav Constitution gave Kosovo (along with Vojvodina) the status of a Socialist Autonomous Province within Serbia. As such, it possessed nearly equal rights as the six constituent Socialist Republics of the S.F.R.Y.

In 1981, riots broke out and were violently suppressed after Kosovo Albanians demonstrated to demand that Kosovo be granted full Republic status. In the late 1980s, Slobodan Milosevic propelled himself to power in Belgrade by exploiting the fears of the Serbian minority in Kosovo. In 1989, he eliminated Kosovo’s autonomy and imposed direct rule from Belgrade. Belgrade ordered the firing of most ethnic Albanian state employees, whose jobs were then assumed by Serbs. 7

In response, Kosovo Albanian leaders began a peaceful resistance movement in the early 1990s, led by Ibrahim Rugova. They established a parallel government funded mainly by the Albanian diaspora. When this movement failed to yield results, an armed resistance emerged in 1997 in the form of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). The KLA’s main goal was to secure the independence of Kosovo.

In late 1998, Milosevic unleashed a brutal police and military campaign against the KLA, which included widespread atrocities against civilians. Milosevic’s failure to agree to the Rambouillet Accords triggered a NATO military campaign to halt the violence in Kosovo. This campaign consisted primarily of aerial bombing of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (F.R.Y.), including Belgrade, and continued from March through June 1999. After 78 days of bombing, Milosevic capitulated. Shortly thereafter, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1244 (1999), which suspended Belgrade’s governance over Kosovo, and under which Kosovo was placed under the administration of the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK), and which authorized a NATO peacekeeping force. Resolution 1244 also envisioned a political process designed to determine Kosovo’s future status.

As ethnic Albanians returned to their homes, elements of the KLA conducted reprisal killings and abductions of ethnic Serbs and Roma in Kosovo. Thousands of ethnic Serbs, Roma, and other minorities fled from their homes during the latter half of 1999, and many remain displaced.

In November 2005, the Contact Group (France, Germany, Italy, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States) produced a set of “Guiding Principles” for the resolution of Kosovo’s future status. Some key principles included: no return to the situation prior to 1999, no changes in Kosovo’s borders, and no partition or union of Kosovo with a neighbouring state. The Contact Group later said that Kosovo’s future status had to be acceptable to the people of Kosovo.

Kosovo declared its independence from Serbia on February 17, 2008. In its declaration of independence. The independence declaration proclaims Kosovo as a democratic, secular and multi-ethnic republic and states that its leaders will promote the rights and participation of all communities in Kosovo. The Declaration also contains a unilateral undertaking to implement in full the obligations contained in the Comprehensive Proposal for the Kosovo Status Settlement (the Ahtisaari Plan) made by Martti Ahtisaari, UN Special Envoy for Kosovo, in February 2007, including its extensive minority safeguards. In the declaration Kosovo invited and welcomed an international civilian presence to supervise implementation of the Comprehensive Proposal, an EU rule of law and police mission and a continuation of NATO’s Kosovo Force. The declaration was adopted unanimously by the members of the Kosovo Assembly that were present. 8

Moreover, The United States formally recognized Kosovo as a sovereign and independent state on February 18. To date, Kosovo has been recognized by a robust majority of European states, the United States, Japan, and Canada, and by other states from the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Shortly after independence, a number of states established an International Steering Group (ISG) for Kosovo that appointed Dutch diplomat Pieter Feith as Kosovo’s first International Civilian Representative (ICR).

Territory and Population

In its declaration of independence Kosovo had declared that its international borders would be as set out in Annex VIII of the Ahtisaari Plan therefore effectively the territory of almost 11,000 km2 that was administered by the United Nations Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK). Kosovo’s population was about 2 million of which 88% were Kosovo Albanians, 6% Kosovo Serbs, 3% Bosniaks plus smaller minorities of Roma and Turks. 9

Source of Image: Lampe, John R., John B. Allcock, and Antonia Young. 2021. “Kosovo.” In Encyclopaedia Britannica

Kosovo’s Declaration of Independence

The first paragraph of the Kosovo declaration of independence was adopted by the provisional institutions of Kosovo on 17th February 2008, reads:

‘We, the democratically elected leaders of our people, hereby declare Kosovo to be an independent and sovereign state. This declaration reflects the will of our people and it is in full accordance with the recommendations of UN Special Envoy Martti Ahtisaari and his Comprehensive Proposal for the Kosovo Status Settlement’. 10

The remainder of the Declaration consists of an announcement of what kind of State Kosovo is committed to be for its citizens and inhabitants –a secular, democratic and multi-ethnic republic, guided by the principles of non-discrimination and equal protection under the law– and for the international community –an international law-abiding State that is committed to peace and stability in the region, that wishes to integrate itself into the European family of States and welcomes a continued international supervision of its democratic development by UNMIK and the EU Rule of Law mission as well as the military leadership provided by NATO . 11

The Preamble of the Declaration sheds light on some factors that seem to have prompted its decision which it understands as a way ‘to confront the painful legacy of the recent past in a spirit of reconciliation and forgiveness’. The following arguments may be of special importance:

-

Kosovo is a special case arising from Yugoslavia’s non-consensual break-up and is not a precedent for any other situation.

-

There have been years of strife and violence in Kosovo, that disturbed the conscience of all civilised people.

-

There have been years of internationally-sponsored negotiations between Belgrade and Pristina over the question of its future political status, but no mutually-acceptable status outcome has been possible, in spite of the good-faith engagement of its leaders.

-

There are recommendations of UN Special Envoy Martti Ahtisaari that provide Kosovo with a comprehensive framework for its future development.

-

In 1999, the world intervened, thereby removing Belgrade’s governance over Kosovo and placing Kosovo under United Nations interim administration. Since then, Kosovo has developed functional, multi-ethnic institutions of democracy that express freely the will of its citizens.

-

It is important to resolve the question about the final status of Kosovo in order to give its people clarity about their future, move beyond the conflicts of the past and realize the full democratic potential of its society.

While each of these arguments may be contested, suffice it to note for the purpose of this study that these are the main arguments that the provisional institutions of Kosovo set forth in the official document in which they declare its independence in order to explain and defend their decision. The fact that the declaration is accompanied by so many reasons shows, if nothing else, Kosovo’s painful knowledge of the contestable nature of the move it made, and could be seen as a general plea for understanding.

III. International Law as Interstate Law?

The Court’s holding in the Kosovo Advisory Opinion

The Court holds in the Advisory Opinion that . . “the scope of the principle of territorial integrity is confined to the sphere of relations between states”. 13

The Court reaches this conclusion as a result of some rather brief reasoning in which the principle of territorial integrity is linked to Article 2 , to the Friendly Relations Declaration and to the Final Act of the Helsinki Conference of 1975.42 While it is true that territorial integrity is expressly mentioned in these provisions and documents and that, originally, they stem from interstate situations, it does not follow logically and necessarily that the principles contained in them only apply in interstate relations. 14

There can be no doubt that the Court was aware of the (many) parts of international law which are either applicable in the internal legal order of states or have no cross-border aspects, or even both if one considers the whole body of human rights law. It follows that the background of the Court’s statement cannot be a general concept of international law as interstate law.

Self-determination because of alien domination? —UNMIK

It might be said that subjecting the people of Kosovo to a period of authority under the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) and the NATO Kosovo Force (KFOR) might somehow itself create a right of external self-determination, and thus a right to independence, under the ‘alien domination’ heading. The main challenge to such an idea is that the policy basis for this category of self-determination is that people who were once free from external control had been made subject to it without any meaningful consent on their part, and that this situation has to be brought to an end unless they agreed otherwise. The problem in Kosovo is that, prior to the UN administration, the Kosovars were not free from external control they were part of Serbia. 15

The power of non-state actors

The Kosovo Advisory Opinion seems to apply the prohibition of the use of force to non-state actors. In a passage in which the Court deals with certain SC resolutions condemning declarations of independence, it distinguishes these resolutions from the underlying situations from the Kosovo case:

The Court notes, however, that in all of those instances the Security Council was making a determination as regards the concrete situation existing at the time that those declarations of independence were made; the illegality attached to the declarations of independence thus stemmed not from the unilateral character of these declarations as such, but from the fact that they were, or would have been, connected with the unlawful use of force or other egregious violations of norms of general international law, in particular those of a peremptory character (jus cogens). In the context of Kosovo, the Security Council has never taken this position. 16

The use of force addressed here may be brought into the interstate paradigm if it is considered as addressing the use of force by other states (in the case of Northern Cyprus: Turkey; in the case of the Republic Srpska: the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro)).

Article 2 (4) UN Charter remains restricted to the interstate situation for other reasons, namely that it contains an obligation for the members of the United Nations. However, that does not exclude the possibility of a customary law principle of prohibition of the use of force to also apply to non-state actors

Foreign Relations

In March 2008, Kosovo passed legislation to establish a foreign ministry. This legislation went into effect on June 15, 2008. The Government of Kosovo appointed Skender Hyseni as its first foreign minister. 17

Recognition and Establishment of Diplomatic Relations, 2008.

Kosovo's unilateral declaration of independence from Serbia, on 17 February 2008, divided international opinion. While the United States and most of the European Union quickly recognised it, Russia, China and many regional powers - such as India, Brazil, South Africa - still regard it as being under Serbian sovereignty. In the years since then, Belgrade and Pristina, along with their respective international allies, have waged a fierce diplomatic battle over recognition. At first, Kosovo made significant gains. However, since 2015, the tide has turned as Serbia has persuaded a number of countries to withdraw their recognition. As a result, there is now considerable confusion over just how many countries actually recognise Kosovo. 18

The United States recognized Kosovo’s independence and agreed to establish diplomatic relations on February 18, 2008, when Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice released a press statement announcing President George W. Bush’s decisions.

After the declaration of independence from Serbia, debate rages over how many states have actually recognised it. Apart from the dispute over the number of initial recognitions, the number of states that have since withdrawn their recognitions (or 'de-recognised' Kosovo) is also contested. 19

Legal consequences of the declaration of independence

Kosovars are not entitled to external self-determination and therefore not the right to be a state. International law required that, were a settlement to be introduced without the agreement of both parties or a binding Security Council resolution, this had to involve preserving Serbia’s sovereignty in the sense of title over Kosovo 20. The reality is that Kosovo's declaration of independence amounts to illegal secession.

The United Nations mission is in a difficult position in that it has not blocked the declaration of independence and yet operates under resolution 1244, which mandates it to administer Kosovo within Serbia. States which recognise Kosovo as an independent state do not necessarily respect their obligations to respect Serbia's sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Legal status of Kosovo

An entity can become a state in law even if its creation is of dubious legality. The main legal criteria for statehood concern, in essence, the practical viability of the entity concerned whether it has a territory, population, and government, and whether it is independent from external control.

The significance of the external self-determination entitlement is that, if it is present, it can tip the balance in favour of statehood even when the entity does not meet the ordinary viability test. For instance, the old colonial states of the period immediately following decolonization and Bosnia and Herzegovina in the first half of the 1990s. Kosovo cannot take advantage of this bias in favour of its conformity to the international legal criteria entitlement to statehood; indeed, the other side of the coin from the presumption in favour of the territorial status quo in international law is, in the absence of special considerations arising out of a right to external self-determination, the presumption against the creation of new states.The main problem in Kosovo as regards the legal criteria of the State is that it is not independent of external control. It is still under the auspices of the United Nations and NATO. The problem legally is that, as a matter of Security Council Resolution 1244 and the Peace Plan agreed to by what is now Serbia, such control is exercised on the basis that Kosovo is part of Serbia, not an independent state. This is a different situation from, say, Bosnia and Herzegovina, where, although OHR 21 exercises certain administrative prerogatives and the state is militarily controlled by EUFOR (European Union Force Bosnia and Herzegovina), this is done on the basis that Bosnia and Herzegovina is an independent state—indeed, its very objective is to positively support that policy. 22

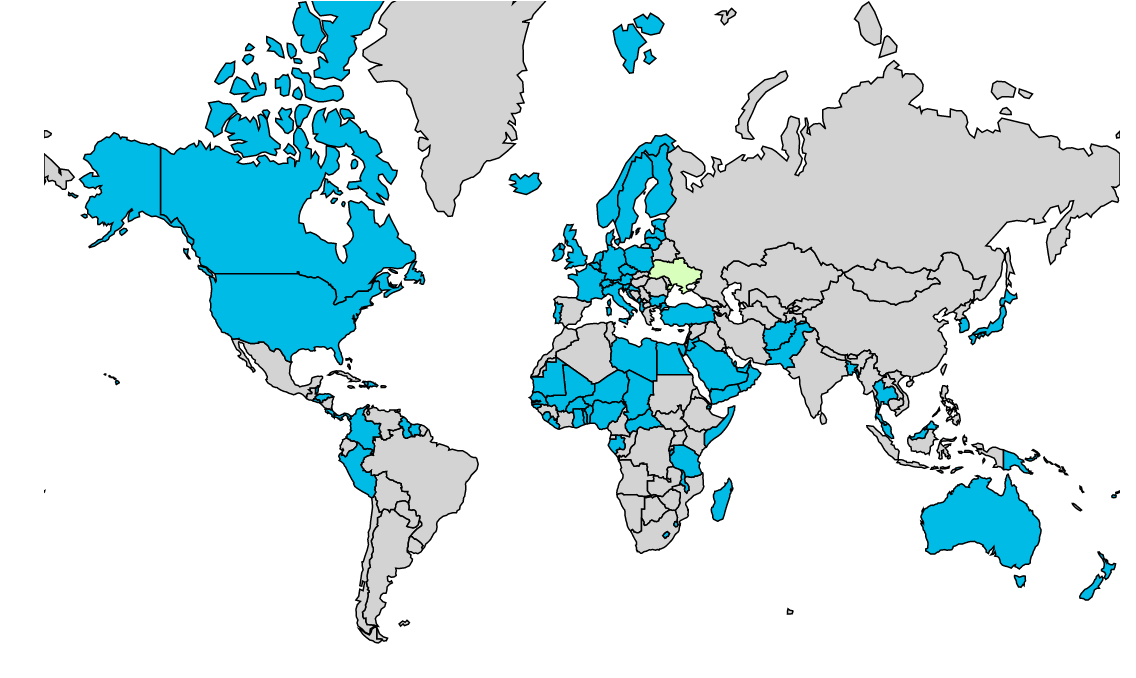

States that recognise Kosovo 2021

As mentioned, Kosovo, officially known as the Republic of Kosovo, is a partially acknowledged state located in south-eastern Europe. Kosovo has partial recognition because of its territorial conflict with the Republic of Serbia.

By March 2020, Kosovo had received 115 diplomatic recognitions as an independent state, of which 15 were withdrawn. Albania, France, Turkey and the UK were the first countries to recognize the independence of Kosovo on February 18, 2008. 23

97 out of 193 United Nations members, 22 out of 27 EU members, 26 out of 30 NATO members, and 34 out of 57 Organization of Islamic Cooperation member state have recognized Kosovo. (As shown in Figure 2)

Source of image: http://read:// https_worldpopulationreview.com /?url=https://worldpopulationreview.com /country-rankings/countries-that-recognize-kosovo.

IV. Discussion

The discussion opened with a debate about the United Kingdom’s sui generis classification of Kosovo’s independence. Gibraltar, the Falklands, Northern Ireland, Eastern Jerusalem and Northern Cyprus were cited as similar situations that refuted the argument that Kosovo was truly unique. It was noted that these disputes had not been resolved academically but were frequently managed, provided the parties did not use force. One participant referred to the tacit agreement between China and Taiwan whereby China does not intervene militarily, with the understanding that Taiwan does not make further declarations of independence. He considered that had the EU aimed in 1999 to reach such an understanding the Kosovan situation would not have escalated in the manner in which it had done.

The meeting then discussed the interaction between law and politics in the recognition of Kosovo, both in terms of justifications and consequences. Politics would continue to play a central role in the recognition of states, since there is no right to recognition under international law. It was suggested that perhaps because the status quo was politically untenable, Kosovo was a case of "circumventing the law for a good reason". One participant argued that, rather than distorting international law, the United Kingdom and other states that acknowledge their position should justify their position in political rather than legal terms. That was the approach adopted in previous interventions in northern Iraq to protect the Kurdish minority and in Kosovo to protect Muslim Albanians. None of those interventions had been authorized by a Security Council resolution due to the threat of a Russian veto. The participant made the recommendation to simply recognize governments.

Explains that recognizing Kosovo was simply the right thing to do, rather than trying to justify their position by supporting arguments that circumvented resolution 1244.

However, there was general agreement that states should explain the legal basis for their recognition of Kosovo. A state would often have to provide a legal rationale. For instance, only legal arguments could refute a charge by another state that the recognition of Kosovo was a violation of international law. Furthermore, Serbia threatened to bring proceedings against the recognition of States before the International Court of Justice. The arguments of Serbia were not yet known, but a recognisable defendant should formulate a legal justification. Although no participant could confirm that the United Kingdom would withdraw recognition if the ICJ found in Serbia’s favour, it was noted that the United Kingdom could be expected to follow any judgment of the ICJ on this point. 24

The political consequences of recognition were now being felt by the European Union, which itself lacked the capacity to recognize a state. It was noted that while the EU agreed that the recognition of Kosovo would fall to national governments, the recognition to date has had implications beyond bilateral. For example, the fact that one third of its members did not choose to recognize Kosovo prevented the EU from complying with the treaties binding the EU Member States. It was also noted that, subject to the Kosovo tribunals, Serbia was in the process of concluding an association agreement with the EU. It would be difficult to enter into an association agreement if the EU and Serbia did not reach an agreement on the status of Kosovo.

Presentations and discussion centred on Kosovo as a European issue. One participant noted the lack of comments about the role and influence of the US in the independence and recognition of Kosovo. It was also noted that the Kosovar Prime Minister was invited to speak to the Security Council in April 2008. Although there had been pressure on the Security Council to deal solely with UNMIK after the declaration of independence, the invitation to the Kosovan Prime Minister was not as controversial as it might seem; the Security Council has the power to invite relevant people to address it, without implications for statehood.

V.Critical Analysis and opinion

In my opinion, the battle of recognition is really a question of leverage. Serbia certainly expects a reaffirmation of its sovereignty over Kosovo. Nor would it really want to. Even during the status talks, international officials asked whether Serbia really wanted to «keep Kosovo if it meant having Albanians around the cabinet table, acting as generals and ambassadors.

However, Serbia also knows that Kosovo cannot be fully accepted by the international community until it has become independent. Belgrade knows that the less recognition there will be, the stronger its negotiating position will be. The problem is that it is a fine line for the Serbian government. If it is too successful, the people might start to actually believe that they can get Kosovo back and reject any final negotiated settlement. In other words, it needs and wants to be successful, but not too successful! That said, it is equally interesting to look at the debate in a Pristina.

While I think many believe that a final settlement with Serbia is not needed, and that eventually Belgrade will have to just give up, I am aware that there are certain people who believe that the recognition battle could yet last for another decade or more and this will prevent Kosovo from joining the UN. They now see the value of trying to reach a final, historic deal with Serbia and wrap it up once and for all. Personally, I do believe in trying to reach a final agreement to end the matter and see Kosovo join the UN. The current situation is bad for Kosovo and for Serbia. Nevertheless, these are my thoughts on it all. I will be really keen to know how the things will turn out in the future for Kosovo!

VI. Conclusion

This article has examined the processes through which Kosovo has secured wide international recognition under conditions of contested statehood and fragmented international support. The article has shown that recognition is not a single political and legal act, but a complex process which needs to be unpacked and critically traced to be able to capture the complex and sometimes haphazard forces and processes that enable or obstruct international recognition.

During and after its supervised independence, diplomatic recognition remains a national priority for Kosovo and certainly the priority for foreign policy. 25 It represents one of the most important aspects for upholding and consolidating, both internally and externally, the sovereignty of Kosovo.

1Accordance with International Law of the Unilateral Declaration of Independence in Respect of Kosovo, Advisory Opinion of 22 July 2010 [2010] ICJ Rep 403.

2Asthana, Subodh. 2019. “How Recognition of a State Takes Place under Provisions of International Law.” Ipleaders.In. June 15, 2019.

3Montevideo Convention on Rights and Duties of States.” 2018. In International Law Documents, 2–4. Cambridge University Press.

4Thakur, Yash. 2020. “Recognition of State in International Law.” Legalstudymaterial.Com. July 26, 2020. https://legalstudymaterial.com/recognition-of-state/.

5Thakur, Yash. 2020. “Recognition of State in International Law.” Legalstudymaterial.Com. July 26, 2020. https://legalstudymaterial.com/recognition-of-state/.

6“Kosovo - Countries - Office of the Historian.” n.d. State.Gov. Accessed December 10, 2021. https://history.state.gov/countries/kosovo.

7“Kosovo - Countries - Office of the Historian.” n.d. State.Gov. Accessed December 10, 2021. https://history.state.gov/countries/kosovo.

8Yefremova, Kateryna, and Ivanna Maryniv. 2020. “Recognition of the state in modern international law (on the example of Kosovo).” Право та інноваційне суспільство, no. 2 (15): 18–22. https://doi.org/10.37772/2309-9275-2020-2(15)-3.

9N.d. Chathamhouse.Org. Accessed December 13, 2021. https://www.chathamhouse.org/Kosovo.

10‘Kosovo’s Declaration of Independence: Self-determination, Secession and Recognition’, ASIL Insights, vol. 12, nr 2,www.asil.org/insights080229.cfm (last accessed 14/12/2021); Colin Warbrick (2008), ‘Kosovo: The Declaration of Independence’, International & Comparative Law Quarterly, vol. 57, July, p. 675-679; and K. William Watson (2008),‘When in the Course of Human Events: Kosovo’s Independence and the Law of Secession’, Tulane Journal of International and Comparative Law, vol. 17, Winter, p. 269-274.

11Almqvist, Jessica (2009) The Politics of Recognition, Kosovo and International Law. Elcano Newsletter (54)

12Almqvist, Jessica (2009) The Politics of Recognition, Kosovo and International Law. Elcano Newsletter (54)

13Borgen, Christopher J. 2010. “International Court of Justice: Advisory Opinion on Accordance with International Law of the Unilateral Declaration of Independence of Kosovo.” International Legal Materials 49 (5): 1404–40. https://doi.org/10.5305/ intelegamate.49.5.1404.

14Dwi Saputra, Yogi, and Ramlan Ramlan. 2021. “Penerapan Prinsip Self Determination Terhadap Pembentukan Negara Kosovo Ditinjau Dari Perspektif Hukum Internasional.” Uti Possidetis: Journal of International Law 1 (2): 193–223. https://doi.org/10.22437/up.v1i2.9867.

15N.d. Chathamhouse.Org. Accessed December 13, 2021. https://www.chathamhouse.org/Kosovo.

16Jacobs, Dov. 2011. “I. International Court of Justice, Accordance with International Law of the Unilateral Declaration of Independence in Respect of Kosovo, Advisory Opinion of 22 July 2010.” The International and Comparative Law Quarterly 60 (3): 799–810. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0020589311000340.

17“Kosovo - Countries - Office of the Historian.” n.d. State.Gov. Accessed December 10, 2021. https://history.state.gov/countries/kosovo.

18“Latest Developments.” n.d. Icj-Cij.Org. Accessed December 10, 2021. https://www.icj-cij.org/en/case/141.

19 “Independent International Commission on Kosovo: The Kosovo Report.” n.d. Reliefweb.Int. Accessed December 10, 2021

20F, Vandome Agnes, Mcbrewster John, and Frederic P. Miller, eds. 2011. 2008 Kosovo Declaration of Independence. Alphascript Publishing.

21“The Office of the High Representative.” 2005. In War and Peace in the Balkans. I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd.

22Littman, Mark. 1999. Kosovo: Law and Diplomacy. London, England: Centre for Policy Studies.

23Andreas. 2020. “International Recognition of Kosovo.” Mappr.Co. December 7, 2020. https://www.mappr.co/thematic-maps/international-recognition-of-kosovo/.

24N.d. Chathamhouse.Org. Accessed December 13, 2021. https://www.chathamhouse.org/Kosovo.

25Newman, Edward, and Gëzim Visoka. 2016. “The Foreign Policy of State Recognition: Kosovo’s Diplomatic Strategy to Join International Society: Table 1.” Foreign Policy Analysis, orw042. https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/orw042.

Bibliography

Books and Articles -

-

Verma, S. K. 2019. An Introduction to Public International Law. 1st ed. Singapore, Singapore: Springer.

-

Luther v. Sagor [(1921)3 KB 532,].

-

Perritt, Henry H., Jr. 2011. The Road to Independence for Kosovo: A Chronicle of the Ahtisaari Plan. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

-

Gioia, Andrea. 2008. “Kosovo’s Statehood and the Role of Recognition.” The Italian Yearbook of International Law Online 18 (1): 1–35.

-

“Independent International Commission on Kosovo: The Kosovo Report.” n.d. Reliefweb.Int. Accessed December 10, 2021. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int /files/resources/ F62789D9FCC56 FB3C1256C1700303E3B -thekosovoreport.htm.

-

“Kosovo - Countries - Office of the Historian.” n.d. State.Gov. Accessed December 10, 2021. https://history.state.gov/ countries/kosovo.

-

“Backing Request by Serbia, General Assembly Decides to Seek International Court of Justice Ruling on Legality of Kosovo’s Independence.” n.d. Www.Un.Org. Accessed December 10, 2021. https://www.un.org/press/en/2008/ ga10764.doc.htm.

-

Borgen, Christopher J. 2010. “International Court of Justice: Advisory Opinion on Accordance with International Law of the Unilateral Declaration of Independence of Kosovo.” International Legal Materials 49 (5): 1404–40. https://doi.org/10.5305/ intelegamate.49.5.1404.

-

Jacobs, Dov. 2011. “I. International Court of Justice, Accordance with International Law of the Unilateral Declaration of Independence in Respect of Kosovo, Advisory Opinion of 22 July 2010.” The International and Comparative Law Quarterly 60 (3): 799–810. https://doi.org/10.1017/ s0020589311000340.

-

N.d. Chathamhouse.Org. Accessed December 13, 2021. https://www.chathamhouse.org/ Kosovo.

-

N.d. Accessed December 13, 2021b. http://read:// https_worldpopulationreview.com /?url=https://worldpopulationreview.com /country-rankings/countries-that-recognize-kosovo.

-

Littman, Mark. 1999. Kosovo: Law and Diplomacy. London, England: Centre for Policy Studies.

-

F, Vandome Agnes, Mcbrewster John, and Frederic P. Miller, eds. 2011. 2008 Kosovo Declaration of Independence. Alphascript Publishing.

-

Newman, Edward, and Gëzim Visoka. 2016. “The Foreign Policy of State Recognition: Kosovo’s Diplomatic Strategy to Join International Society: Table 1.” Foreign Policy Analysis, orw042. https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/orw042.

-

Andreas. 2020. “International Recognition of Kosovo.” Mappr.Co. December 7, 2020. https://www.mappr.co/thematic-maps/international-recognition-of-kosovo/.

-

Thakur, Yash. 2020. “Recognition of State in International Law.” Legalstudymaterial.Com. July 26, 2020. https://legalstudymaterial.com /recognition-of-state/.

-

Grant, Thomas D. 1999. The Recognition of States: Law and Practice in Debate and Evolution. Westport, CT: Praeger.

-

Almqvist, Jessica (2009) The Politics of Recognition, Kosovo and International Law. Elcano Newsletter (54)

Conventions

-

Montevideo Convention on Rights and Duties of States.” 2018. In International Law Documents, 2–4. Cambridge University Press

-

“The 1986 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties between States and International Organizations or between International Organizations.” 2014. In The Institutional Veil in Public International Law: International Organisations and the Law of Treaties. Hart Publishing.

Websites

-

https://www.un.org/

-

http://www.bbc.com/

-

https://www.asil.org/

-

https://www.mfa-ks.net/en/politika/483/njohjet-ndrkombtare-t-republiks-s- kosovs/483

-

https://www.mappr.co/thematic-maps/international-recognition-of-kosovo/

-

https://www.chathamhouse.org/ Kosovo

-

https://www.britannica.com/

About the Author:

Anshu Singh is political science graduate from IPCW, Delhi University. She is currently pursuing master's in Conflict Analysis and Peacebuilding from jamia Milia Islamia. Her areas of interests are gender,international law,diplomacy, Latin American studies ,African studies ,conflict security etc

Note:

The article reflects the opinion of the author and not necessarily the views of the Organisation.

Share this article:

© Copyright 2025 Indic Researchers Forum | Designed & Developed By Bigpage.in